“An election that only one party wins, with a simple plurality, operates as a kind of factory setting for American democracy, one that we have neglected to update, despite radically changed circumstances.”

This week’s New York Times opinion piece on How to Fix America’s Two-Party System is a fine read, and not just because of clever metaphors (as above) and some gorgeous scrolly graphics. Authors Jesse Wegman and Lee Drutman also clearly lay out how “two parties competing in winner-take-all elections cannot reflect the diversity of 335 million Americans.”

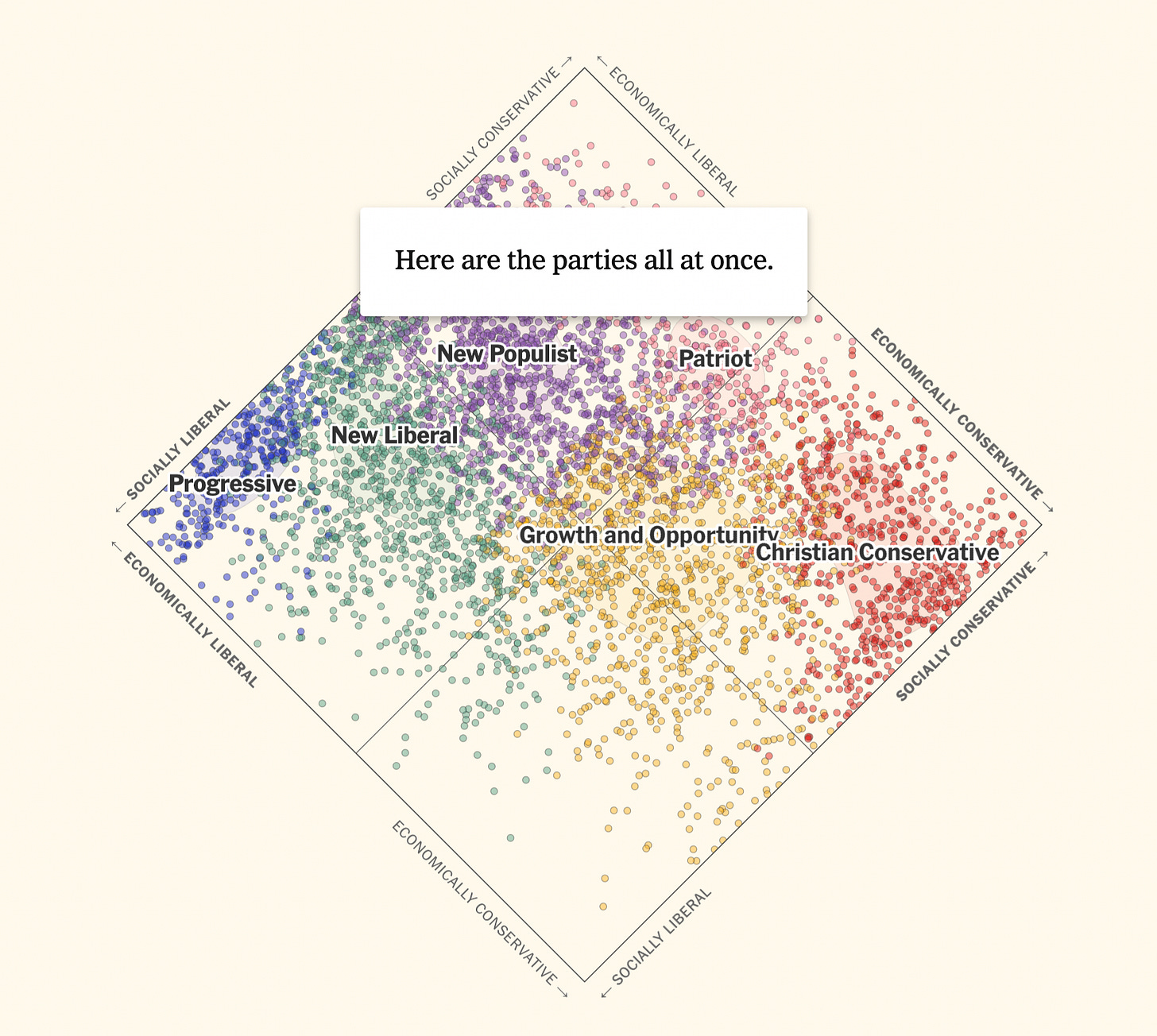

A graphic tellingly portrays six main groups of US political sentiment that might form the basis for future parties (one slide can be seen below). The advocacy for more members of the House of Representatives is spot-on (a congressperson now represents on average 760,000+ people). And the case against single-seat, gerrymandered constituencies is well put. After all, the authors point out that 90% of seats are “not competitive”, that is, they are won by a landslide. Voters therefore almost never chose the winning candidate, but one of the two current parties does.

No doubt, proportional representation is better than winner-take-all elections, just like an aristocracy is usually better than one-person rule, or a law-abiding king may be better than an oppressive tyrant. Wegman and Drutman are right to point out that in many other states, notably in Europe, this way of allowing many and more varied parties to win seats in parliaments produces more representative government.

“An exact portrait”

To define the ideal representation that democratic reformers are aiming for, the New York Times authors do well to cite John Adams. The US founding father wrote in 1776 that the US Congress “should be in miniature, an exact portrait of the people at large. It should feel, reason and act like them.”

My late father Maurice Pope had the same ideal for representation when he considered the pros and cons of proportional representation in his posthumous 2023 book The Keys to Democracy: Sortition as a New Model of Citizen Power. He shows how proponents of this system go back to mid-19th century figures like English philosopher and politician John Stuart Mill and Charles Dodgson, an Oxford mathematics don who enjoyed thinking up new systems of electoral representation (when not writing children’s stories like Alice in Wonderland under the pen name Lewis Caroll).

Maurice Pope’s conclusion is that proportional representation can never get far toward to this “exact portrait” of society, even if it is an improvement on winner-takes-all elections. The book’s central argument, after all, is that systems based only on voting favour the wealthy and well-connected, concentrating power in the hands of factions and the few. This line of thinking also goes back a long way, from the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle to writers in the 20th century like Italian-German political sociologist Roberto Michels. Here’s an excerpt from The Keys to Democracy:

Proportional representation is not a recipe for introducing democracy, but for improving oligarchy. Its tendency is to make government more responsive to the will of the broad majority and to dampen the mad swings of two-party politics. These are both desirable ends. It also encourages an increase in the number of effective political parties. From the liberal point of view, this is a good thing too. If the ideal is for as wide a range of serious opinions as possible to be represented in political debate, then four or five parties are as much an improvement on two parties as two parties are an improvement on one.

But from the democratic point of view, it is a red herring. Proportional representation still works through political parties. Indeed, it gives them and their organisations even greater importance. The main parties will play a steadier part in government than with a system of alternating periods of office and the small parties will also be able to exercise a genuine influence on events. If parties become more powerful, so do the party-organisers.

The consequence is inevitable. The individual voter’s effectiveness will be strengthened and so will the grip of Michels’ “iron law of oligarchy”. This would be a paradox if voting were a democratic device. As soon as one realises that it is not, the paradox vanishes and becomes a truism. What strengthens an electoral system must also strengthen an oligarchic one, for they are two sides of the same coin. (pp. 22-23).

A lottery winner

Since elections deliver such poor results, Maurice Pope and many in the new movement for deliberative democracy argue, a better way to achieve best-in-class representation is by using sortition, that is, the random selection of regular citizens to decision-making bodies. The world now has a version of this, citizens’ assemblies, of which more than 1,000 have been held in the past decade. Groups of 20-200 citizens are chosen by lot to meet on a tough policy question, inform themselves from experts, deliberate as a group and build up a new policy based on what most participants agree on.

Such representation is still far from perfect. This new method of taking decisions is still little known, so typically only 5% of randomly issued invitations get a positive answer. That means that there is a second lottery (known as stratification) to choose from among those who say “yes”. This makes sure the profile of participants in the assembly matches the make-up of their community. To get closer to the “exact picture” would need a legal requirement to attend, as happens with jury service.

So much for representation. Another issue beyond the scope of this article is Wegman’s and Drutman’s idealistic hope that several new parties would be able to easily make compromises on policies and form governments. Chronic difficulties right now around exactly this issue in the proportional systems of Germany, France, the Netherlands and Belgium point to grave potential obstacles here.

Back to utopias

It’s wonderful, though, that The New York Times is debating such constitutional questions on its opinion page. My late father always regretted the absence of constitutions and utopias from political debates over the past 200 years.

Such constitutional speculation was common in the Renaissance, becoming highly influential in government design during the American and French Revolutions. One sign of the un-fashionability of such talk today is that – amid the glowing reviews of The Keys to Democracy – there’s some disapproval of the chapter in which Pope develops his own political utopia. More encouragingly, however, I’ve heard that one Ivy League university has assigned students precisely this chapter from the book as part of a politics course on new ideas.

My eyes rolled too when I first read the manuscript in the 1980s. I am ashamed to remember my exasperated comments like: “Dad, what planet are you living on?” But I now love the story of his utopia, a community of scientists that organises itself when marooned on Antarctica after a nuclear war lays waste to the rest of the world. The scientists experiment and gradually build a completely new political system in which executive, legislature and judiciary take decisions entirely in randomly selected assemblies.

My late father admits that in normal circumstances, no society starts from scratch, so in reality such structures can only evolve. But ideals serve a motivational purpose, even if they take time to materialise and rarely in exactly the form we expected. It is at the very least refreshing to read about “a community that had discovered how to live at peace with itself and that had cured itself of the fatal human disease whose first symptom is group loyalty and which ends in blindness and mutual destruction” (p. 164).